In 2006, Clive Humby, a British mathematician, coined the phrase “Data is the new oil”. The phrase’s initial intent was to demonstrate that data is one of the most valuable resources to an organization in a digital economy. Inevitably the analogy has been extended to sow fear, uncertainty and doubt (FUD), as the cybersecurity industry equates the impact of failing to secure data with the brutal impact that oil drilling and use has on the environment.

As Casey Ellis from Bugcrowd highlighted on LinkedIn, there does seem to be an active search for a new analogy that raises the FUD factor even more. “Data is the new Uranium” surely conjures images of the fallout of nuclear war for everyone—not a comfortable image in light of recent world events.

Sadly the use of FUD messaging like “Data is the new uranium” is still commonplace in cybersecurity; and while it might work short term to sensationalize a topic, it fails long term. You scare people often enough with FUD and people just stop paying attention to the “boy who cried wolf”. That may, in fact, be what is driving the urge to replace a 16-year-old analogy that was derived for an entirely different purpose with something more dangerous.

The search for a new “Data is Dangerous” analogy does raise two interesting and interlinked questions:

When did data become so dangerous?

The surprising answer, particularly hearing it from a data security vendor, is that data hasn’t become more dangerous. Data is, and will remain a valuable resource that should be protected, because of its value to the organizations that collect it as well as those it was collected from. You might argue that as a valuable resource, data-rich organizations also suffer the “resource curse” like many (even most) countries that are rich in natural resources. As highlighted by my colleague Sachin Tyagi, these countries, although rich in resources, tend not to do so well in other indicators of economic or democratic development. Like natural resources, it is illogical to believe that data is dangerous for those who have it, simply because it is data. Neither data nor resources become dangerous on their own; instead they become so based on the actions, attitudes, and sometimes inaction of others.

Data becomes dangerous or risky when:

- Someone who isn’t supposed to have access has access to data;

- Someone does something to data to prevent an organization or person from legitimately using it;

- Someone changes data in an undesirable way; or

- Someone does something illegal or unethical with the data.

Data also has the potential to become dangerous when we don’t know where it is or what type it is.

You will notice that in all the above scenarios there are three constants:

- Data—It’s important to know where and what data you have.

- A person (identity)—That someone could be you, your employee, your supplier, or in the worst case scenario, a cybercriminal.

- An action or operation—The action can be something as innocent as reading the data or even storing the data in the wrong location.

This combination of data, identity, and operations is what we focus on at Symmetry Systems—not because data is dangerous—but because it reduces fear, uncertainty and doubt. In each of the danger scenarios, the simplicity of the statements means it is possible to imagine a more positive approach. You can imagine successfully preventing, detecting, and responding before each of those scenarios become real—an approach that isn’t possible when having to first deal with the FUD of imagining the average person figuring out nuclear physics and uranium.

How should we view data instead ?

We’ve discussed this idea of “how should we view data” at length within Symmetry Systems; and the opinions expressed were just amazing. It is clear to everyone at Symmetry that data is not just something waiting to go wrong.

When I talk about data with my colleagues—it is clear that our goal is to protect not only our personal and corporate data, but also the data about our customers, the data belonging to our customers, and the data about their customers.

Every company needs to embrace data not only as a valuable resource solely for their use—but also as a resource generated by, about, and from every stakeholder connected to the organization. When we look at data and what it tells us, we recognize that it’s data about so much more than an organizations—it’s data about the customers, the team, the product, and the combined success. It’s not a big leap to consider that data as information about your family; and naturally we would want to treat the data with the same principles that we treat our family. So perhaps, it’s time to adopt a new view of data:

Data is like your family.

Treat it with the same respect, care, and deliberation.

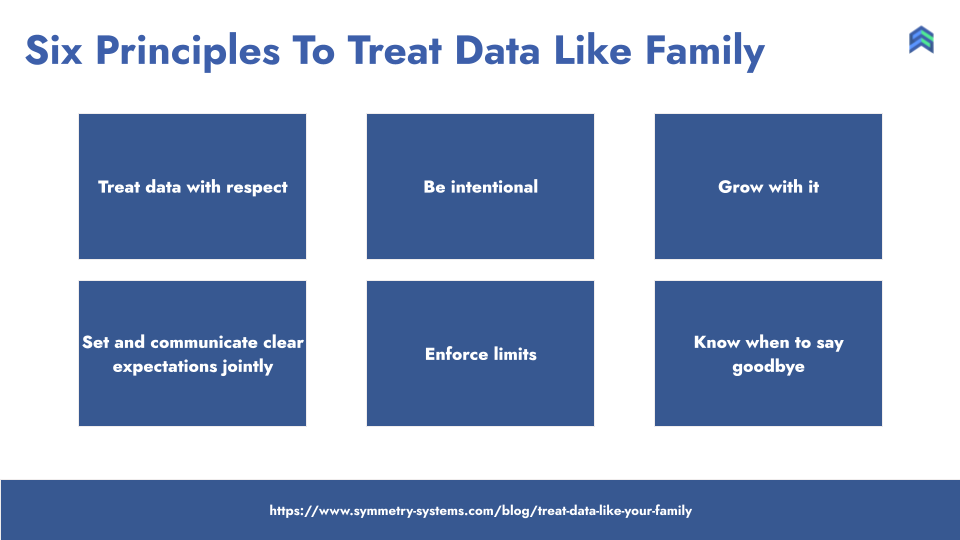

Six Principles to Treat Data Like Your Family

While we were exploring this concept, it became clear that while it resonated with everyone, everyone had a nuanced view of what “family” meant—from the rambunctious child to the embarrassing uncle that no one likes. It was also clear that by starting with this concept, there was a set of principles that could and should be adopted by every organization who cares about their customers, their people, their products, and their combined success.

Principle 1: Treat data with respect.

Treating data with respect means treating data like we would expect others to treat our data or how they expect we should be treating it; whichever is the higher bar.

Principle 2: Set and communicate clear expectations jointly.

Setting and communicating clear expectations means actively trying to understand and agree, or at least be emphatic to the needs and expectations of the customers, employees, regulators, and other stakeholders that have interest in the data being held.

Principle 3: Be intentional.

Too often data governance is an afterthought in which we deal with the implications of not factoring into our decision-making how much data we create, collect, store, use, process, or delete. Data and privacy engineering and privacy by design can help proactively address this within the systems we build, but should also be extended to consider how we monitor the use of data is in line with our expectations.

Principle 4: Enforce Limits.

Enforcing limits requires defining and enforcing guardrails, to reduce the likelihood of something going wrong, and seatbelts and other safety features, to reduce the impact if it goes wrong.

Principle 5: Grow with it.

Data is dynamic and is constantly changing. Organizations need to adapt and grow as their data evolves; but also by deriving more value securely from data, organizations can accelerate their own growth.

Principle 6: Know when to say goodbye.

Too often organizations hold on to data for too long. Goodbyes are always difficult. Rather than being concerned about saying goodbye too soon, saying goodbye to data is an opportunity to end our relationship in the best possible way with consideration of all the implications. More importantly, it also signifies we can say goodbye and still be all right.

As we head into the holiday season, I hope these principles resonate with you and you look to find ways to put them into practice. If you want to find out more how we put these principles into practice, please do not hesitate to reach out to me or the Symmetry team.